4th September 1914

The 5th Division held a Divisional Conference at 10am in Bouleurs. From here it was decided that the 15th Brigade was to act as rearguard. They were to be arrive at Gagny at 9am the following morning.

False alarms continued to keep everyone on tenterhooks. Gleichen reports that he responded to reports of enemy by pushing up the outposts of the Bedfords along with a couple of howitzers attached to his Brigade.

The Dorsets remained in bivouac for the whole day. It wasn’t until 11:45pm that they finally continued the retreat.

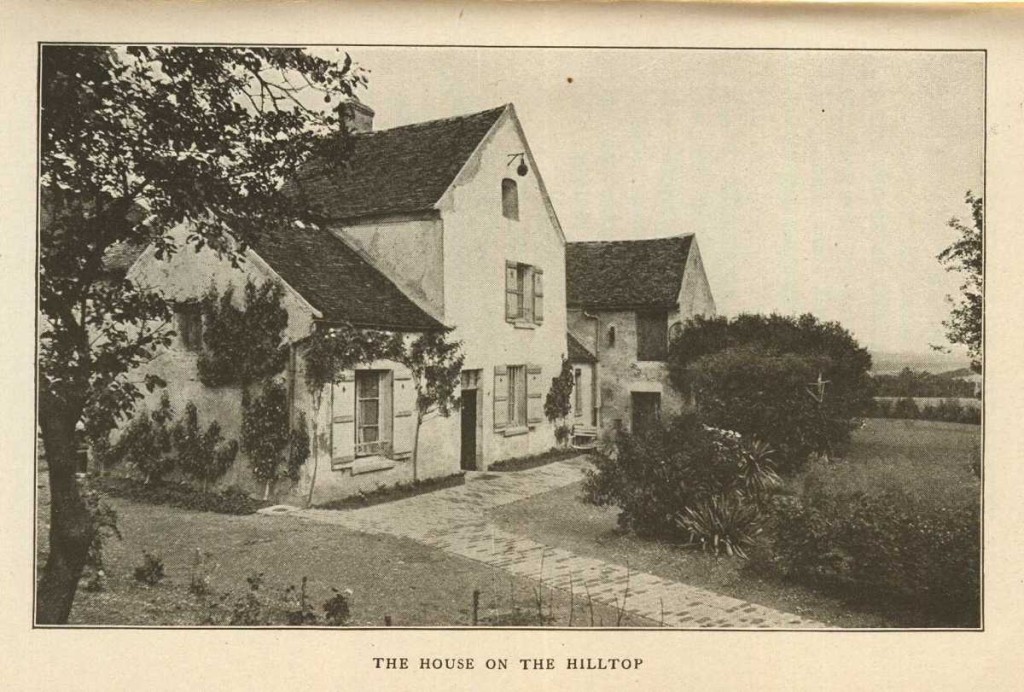

The Bedfords were pushed right up to the southern edge of the Marne. There’s an interesting narrative by Miss Mildred Aldrich, an American who was living in Huiry, high above the valley floor. She wrote a book about her experiences called “A Hilltop on the Marne“. She had spotted Uhlans, mounted German cavalry, down in the trees beside the Marne, and had reported it to Captain Edwards of the Bedfords who arrived on the 4th September. All the British (or English as she refers to the entire BEF throughout the book) seem to be interested in was food.

It was not much after nine when two English officers strolled down the road—Captain Edwards* and Major Ellison, of the Bedfordshire Light Infantry. They came into the garden, and the scene with Captain Simpson of the day before was practically repeated. They examined the plain, located the towns, looked long at it with their glasses; and that being over I put the usual question, “Can I do anything for you?” and got the usual answer, “Eggs.”

More evidence of the 15th Brigade’s lack of personal equipment is confirmed by her line “these Bedfordshire boys were not hungry, but they had retreated from their last battle leaving their kits in the trenches, and were without soap or towels, or combs or razors”.

The story is expanded upon in 1914 by Lyn Macdonald but Mildred Aldrich’s personal account is much better reading. She wrote several books about her experiences in Huiry during the First World War.

*Sadly Captain Edwards was injured in October and later died of his wounds in hospital at London Bridge on 31st December 1914. There’s an online memorial to him here. Interestingly he was born in Brixton. On the other side of the tracks to our Frank mind you.