10th October 1914

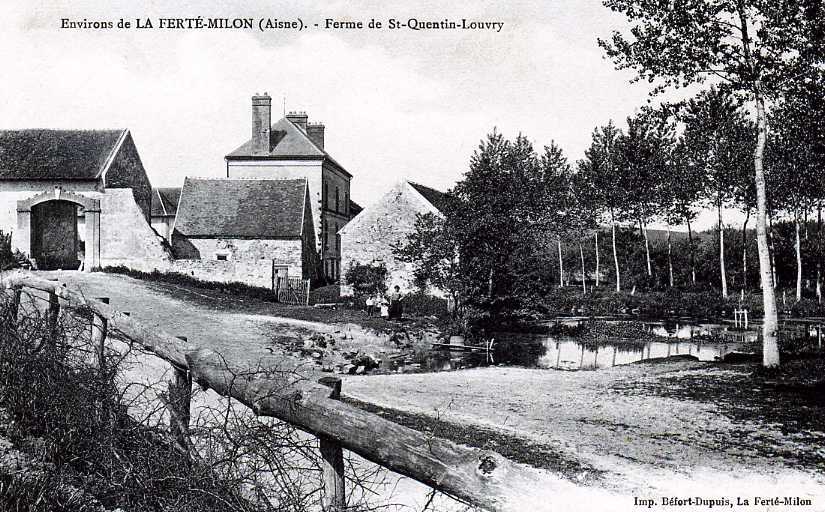

After more waiting, and much to-ing and fro-ing, the buses finally arrived at about 2:30pm and took them via the town of Saint-Pol-sur-Termoise and dropped them off at their billets in La Thieuloye.

The BEF was hurtling towards the west now as fast as they could go. It was hoped they could reach Lille in time, which was about 40 miles off to the north east, but Gleichen wasn’t so sure. He had witnessed thousands of young men streaming to the west away from the possibility of being interned by the advancing Germans.

Frank was known as Biddy or Bid. Nicknames are cryptic, often born from the language a group of friends or family form through familiarity. Sometimes they came from acronyms of initials (see my theory about the origins of Auntie Muff yesterday). Biddie certainly isn’t that. His initials are AFC. So where did it come from?

Biddy is an old 16th Century name for baby chicken. The origin is suggested as perhaps imitative of the chicken, so perhaps it was used as a calling sound when feeding them. A chickabiddy is an affectionate term for a small child. I think this is the most likely origin of Frank’s nickname.

Strangely enough, Biddy came up again when I was looking up references to Frank’s mention of the word “lizzie”.

“No cold tea out here or little drops of lizzie (?), could do with a drop of cold tea now.”

I’ve previously opined that cold tea was beer. I’ve subsequently read that it referred to brandy. I must opine less. But I think it’s a pretty interchangeable phrase. Here, Frank’s probably referring to the hard stuff. I initially thought that lizzie was some kind of Babycham. But I am pretty sure it’s a reference to Lisbon wine, which was some kind of very cheap fortified wine or at least a collective noun for any cheap wine. Empire Wine is often mentioned. Wine of such unconscionable filth that they could only sell it back in Britain. It’s fair to say that cheap wine was popular in Edwardian times. It was perfect for getting drunk really quickly, which tends to be a good property for booze. Britain in the early 1900s is no different from today when it comes to drunkenness.

The quality of Lisbon wine was debatable and its reputation for potency didn’t stop here. Not strong enough for the real diehards, it was often mixed with cheap alcohol like methylated spirits to produce a truly lethal drink called “Red Lizzie”. Yes, that’s the stuff you clean your brushes with. When produced from red wine it was know as, wait for it, “red biddy”. Was Biddy a massive booze hound and that’s how he got his nickname? Had he accidentally signed up after a weekend of too many red biddies?

Red biddy was a drink of legend that by the Second World War had largely vanished from pubs and was made at home. It rendered the drinker blind drunk and often mad. It wasn’t surprisingly compared to absinthe that so afflicted Parisians in the 19th Century. Government laws like the 1937 Methylated Spirits Bill tried to control this dangerous substance, and this report by the Medical Officer of Health for Wandsworth in 1936 highlighted the concerns that many social organisations, such as the Salvation Army, lobbied the Government with.

The Government are still struggling today with adulterated alcohol. A 2008 Guardian article highlights the rise in theft of alcoholic sanitisers from some London hospitals. It is used as a base for “the street drinkers’ favourite ‘red biddy'”. Delicious and health conscious too!

The great Kingsley Amis recommends red biddy as part of a decent breakfast in his booze-befuddled novel Lucky Jim.

The three pints of bitter he’d drunk last night with Bill Atkinson and Beesley might, by means of some garbaged alley through the space-time continuum, have been preceded by a bottle of British sherry and followed by half a dozen breakfast-cups of red biddy.

I prefer Alpen.

Let’s leave this subject with this fine English gentleman describing the appeal of pure alcohol very eloquently.