9th September 1914

In 1914 the commander of a battalion had access to a remarkable arsenal of technology to help them locate and fight the enemy. They had machine gun sections, long and short range artillery, plane spotters, telephones, metalled roads, railway lines, motorcycle dispatch riders and engineers. These were all used to help the soldier on the ground understand, outmanoeuvre and engage the enemy to his advantage.

On the ground, however, in the “fog of war”, it was often much more confused. There were many reasons why these new technologies failed the soldier in 1914. Planes couldn’t fly because of the weather. Artillery was unable to find a safe spot to fire from. Different units became mixed up in battle. Roads were blocked with all kinds of traffic. Telephone lines had been cut. The list goes on and on. Despite all these failings, offensives still went ahead. More often that not this had catastrophic results.

Today we’ll see this “fog of war” in action. And we’ll see, what I think is, the main failing of ground forces in 1914: Units carrying out unsupported full frontal attacks against concealed machine guns and artillery. This approach to offensive tactics was already killing soldiers by the tens of thousands*. The Dorsets experienced this for the first time on the 9th September 1914.

The Dorsets advanced in the morning, heading north through Saârcy-sur-Marne and crossed its bridge to Mery-sur-Marne. The 5th Division had established a bridgehead across the river at 9am. There was the sound of heavy gunfire up ahead of them where the 14th Brigade were pushing on ahead.

The River Marne, at this point in its course, runs in tight loops, through deep valleys which climb sharply through farmland up to heavily wooded hilltops. One of these hilltops, Hill (or point) 189 was reportedly in the possession of the 14th Brigade, away to their left. At least that’s what Divisional Staff told Gleichen when he met them for a “pow wow” at what he repeatedly called Merz, but must have been Mery(-sur-Marne). Here the 5th Division instructed the 15th Brigade to support the 14th Brigade who’d got hung up somewhere to their left towards the Montreuil Road.

The Brigade advanced east towards Le Limon, using the slope and the woods as a shield from possible enemy attack. Gleichen reports that “when we emerged from the woods there was a Prussian battery on the hill.” Here was the first mistake. Why did they assume that this was a “deserted” battery? The Dorsets’ war diary remembers “this battery had been reported as deserted”. Did Gleichen assume too much here? Whatever the mistake it would have been prudent to reconnoitre. But they didn’t. The 15th Brigade moved into the open in column file. As soon as “not more than a battalion had got clear, when the “deserted” battery opened fire and lobbed a shell or two into the Bedfords and Cheshires”. The Germans were cleverly concealed nearby, ran out fired their guns and then ran and hid again. Gleichen ordered a howitzer battery to return fire which he said silenced the battery.

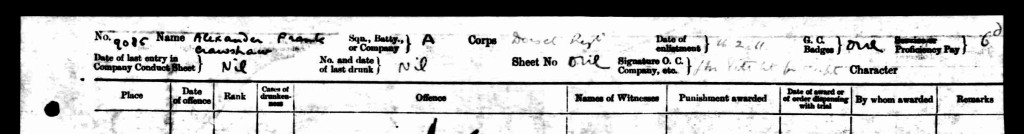

The Dorsets were in the vanguard and Lieutenant Colonel Bols immediately volunteered to attack the hill, which was “only a rise” according to Gleichen. The enemy could be seen digging trenches on the ridge. After a reconnoitre it was agreed that the Dorsets would attack. By now, the Dorsets had formed up at a farm about half a mile north of Le Limon. They formed into attacking lines: D Company on the left and C Company on the right, with A Company and the Machine Gun Company in reserve. B Company was currently detached from the Battalion as vanguard to the Brigade Headquarters.

It took about an hour to reach their positions through a wood and by 2:20pm they had reached the road between Pisseloup and Genevrois. A message was sent by Bols to 15th Brigade HQ. “I shall attack shortly. What artillery support may I expect?”. None came. Undeterred, the Dorsets moved forward again into a firing line. B Company now rejoined the battalion, at the request of the Brigadier General, and started to edge its way around the west of Bois des Essertis.

At 3pm all hell broke loose. Machine guns and rifles opened up from Germans hidden in the surrounding trees. Shellfire rained down from the battery on Hill 189. The entire brigade was immediately pinned down. At this point the Dorsets tried their best to move forward under withering fire and return it as best they could.

B Company did well at first through the woods but the mortal woundings of its commander, Captain Roe, and of his newly arrived second-in-Command, Captain A.B. Priestley, whom we met on the 5th September, soon put a stop to their advance.

D Company was pinned down in open fields. Machine gun fire swept their attack lines and just after 4pm one of their platoon comanders, Lieutenant Athelstan Key Durance George (another Brixton-born Dorset), was shot in the head when he raised himself to look through field glasses. Major Saunders, the Company Commander, was also wounded but he carried on regardless. The war diary reports that he “behaved with great gallantry and exposed himself frequently”. The Dorsets simply couldn’t move under the amount of incoming fire. There was nothing at their disposal to overcome this situation they found themselves in. At no point did the Dorsets received any covering fire from supporting artillery. What happened to that howitzer battery Gleichen put to good use just a couple of hours before? There’s no mention of them in any other the other first hand reports.

A Company and Battalion HQ were also stuck where they lay, behind C and D Companies. At 4pm shellfire from an enemy Field Howitzer Battery added to their misery. At 5pm Bols received verbal orders from Gleichen for the Dorsets to retire once it was dark. The two sides exchanged fire like this until 6:30pm when the Dorsets withdrew from the deadlock to hastily dug trenches and bivouacs west of Bézu-le-Guéry to the east of Hill 189.

At 9pm the Battalion was informed that the enemy had now retired. The Dorsets received their order to march once more at 4:30am the next day. The Germans were now fighting a rearguard action and doing it very cleverly.

The diary records that the Battalion lost 3 officers (although none of them died that day), 1 wounded and 7 men killed with 31 wounded and 4 missing. A search of the CWGC shows 10 dead for the 9th September 1914.

* I’m not saying they were wrong in their approach. I think it is important that we don’t impose our knowledge of subsequent history upon people’s lives in 1914. There was no real experience of this kind of warfare at the time. Technology and tactics took a very long time to catch up on equipping a soldier against a modern army with such destructive power. There were no grenades or mortars for small scale attack like this one and the machine gun was seen as very much a defensive support weapon at this time. The British soldier didn’t even get a tin hat until late 1915.