14th September 1914

The rest of the brigade followed the Dorsets across the River Aisne over the next few hours. Captain Johnston and Lieutenant Flint continued to punt troops across and ferry back the wounded. They did this under constant shellfire throughout the day until 7pm. Johnston was awarded the Victoria Cross for his part in this extraordinary feat, Flint the DSO. We’ll meet the inimitable Captain Johnston again, later on in the year.

At 4am the Dorsets, acting once more as advanced guard, headed to Sainte-Marguerite via Bucy-Le-Long, where they took up shelter in a sunken road. The enemy’s shellfire had increased in intensity. Gleichen recalls “the enemy’s artillery had meanwhile opened on us, and shells began to crash overhead and played the devil with the tiles and the houses. But they did not do us much harm.”

In fact the Dorset diary reports that at around 12pm 3 shells hit them in the sunken road causing casualties. The Dorsets’ diary records 1 dead and 20 wounded that day. The CWGC records 3 dead on that day who were subsequently buried at La Ferte-sous-Jouarre. The additional two deaths could easily have died from wounds received previously, like Lieutenant George who sadly died today in Coulommiers military hospital. Another man, Private A.R. Pearce, passed away at Royal Victoria Hospital in Netley, Southampton.

Gleichen claims that the Dorsets “were our leading battalion, and they were pushed on to help the 12th, and filled a gap in their line on the hill above the village front at the eastern end.” The Dorsets’ diary is more vague and simply states that they were in touch with the 14th Brigade on their right and the Essex Regiment was to their left. The Dorsets remained here for the rest of the day. We’ll come back to them tomorrow.

The rest of the 15th Brigade had been ordered to attack the Chivre spur and then push onto Condé beyond it. Gleichen raises his eyebrows with the comment that this is “rather a ‘large order.'” The Chivre spur was one of many fat fingers of land that pushed out into the banks of the river Aisne below. It rose impressively for 400 feet with densely wooded sides. This high ground needed to be taken in order to join I Corps on the left hand of the BEF with II Corps on the right. The attack, without close artillery support, was difficult enough but there was another problem.

The Franco-Prussian war of 1870 ended in a total thrashing for the French. One of their military responses was to build a large amount of fortresses along key strategic points; a ring around France itself and then a series of forts defending Paris. One of these stood at the top of the Aisne right at the tip of the Chivre spur. It was called Fort de Condé and is still there today, testament to its enduring strength. The Germans used it to their full advantage reportedly housing three artillery batteries in its walls. It later became a hospital and remained in their possession until 1917. None of the British accounts mention this fort. With it, the Germans had an almost impregnable hold on the spur.

The entrance to Fort de Condé, taken by Flickr user Geneviève Prevot

Meanwhile Gleichen gathered his troops along with stragglers from the 14th and 13th Brigades. The attack on Chivre spur was launched from Missy quite late in the day at 4:30pm but soon broke down in utter confusion. Some men attacked their own troops by way of a horsehaped track leading them back towards their own lines. Other men were trapped by 6 foot high wire enclosures in the woods. They never stood a chance against such overwhelming odds. Eventually the British fell back in disarray, chased by shrapnel rounds, rifle and machine gun fire, and hid behind Missy’s ancient, thick walls. The Norfolks, in particular, suffered badly, with 37 men killed.

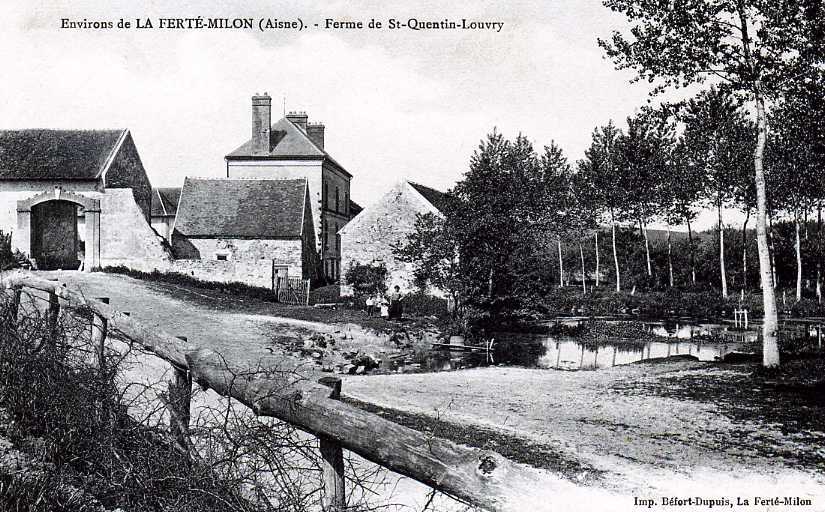

The Brigade Headquarters withdrew a little further to the south, to a farm called “La Biza”. It’s still there today and is a now B&B. I’ll leave you with Chef Gleichen’s final thoughts on the day’s action.

We bought, murdered, and ate an elderly chicken, but otherwise there was devilish little to eat except a store of jam, and we had only a very few biscuits and no bread.