Dateline Belfast 13.8.14. Letter in pencil

Dear Till

Many thanks for your welcome letter which I thought was about time. Pleased to hear that you enjoyed yourself and also had lovely weather. Sorry to hear about May not being able to go with you, I hope her mother is better by now and ask her to drop me a few lines for I am still waiting dont forget to tell her. Is that what they are saying go to Ireland for a “quiet holiday”, you should come over here there is just as much excitement here as any where else. Give my love to all at home and tell Aunt I was ever so pleased to hear from her and glad to see they are alright. We are off on Friday to the War, we don’t know where we are going to the ship is ready for us and it is rumoured we are going to Belgium but I cant say exactly where we are off to. We have been working as hard as we can, getting every think ready for when we go on Friday. Now Till dont get worrying about me for I shall be alright, and I hope you will. Now Till when you send that photo and write to me which I hope will be soon (put the address 1st Dorset Reg Belfast) or elsewhere, and what will find me. Yes Till drop her a few lines for I am sure Jess would be pleased to hear from you, and she would answer your letter and only be too please to. Her address is 14 Maralin Street, Antrim Road Belfast, now dont forget to write to her soon. Now Till I think this is all the news at present hoping you are in the pink Tell Aunt I will drop her a few lines soon so will now conclude hoping to hear from you soon.

I remain

Your loving Brother

Bid

xxxxx

Britain enters the War

On the 4th August 1914 Germany invaded Belgium. Great Britain responded with an ultimatum, which expired, unanswered, at 11 o’clock GMT. As a result, the two nations were at war.

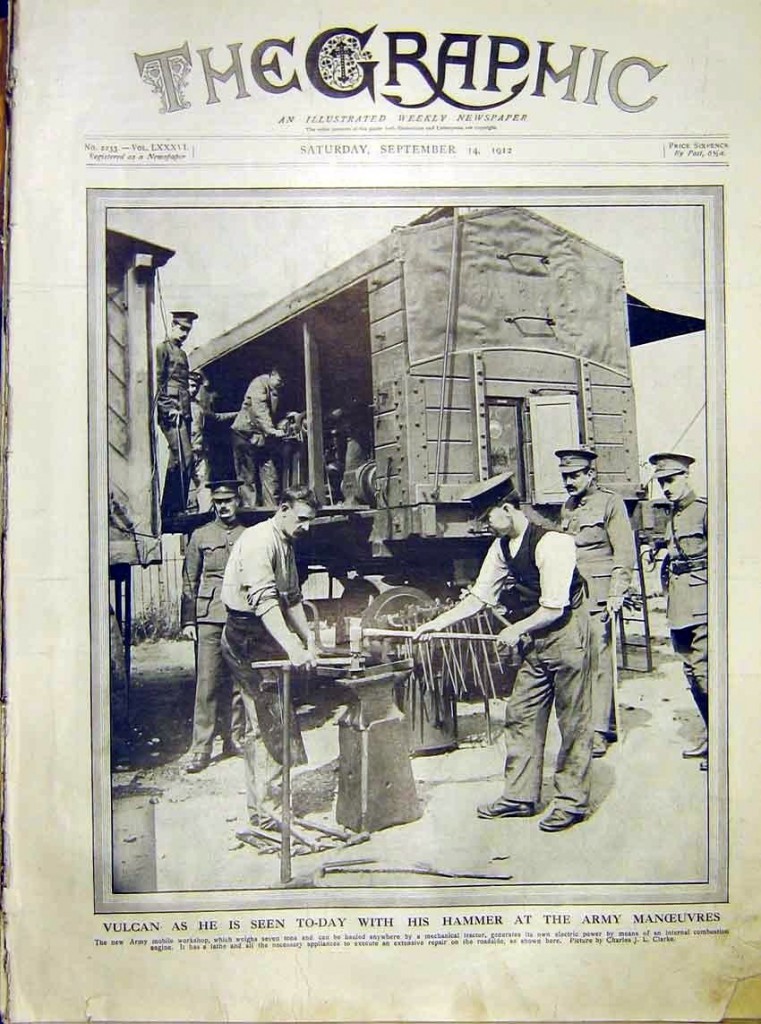

Immediate plans for mobilisations had been carefully planned out in the War Book: a series of documents meticulously detailing plans for mobilisation.

In Belfast the Commanding Officer (CO) of 1st Bn Dorsets, Lieutenant Colonel Louis Jean Bols, received his mobilisation orders at 5:39pm on the 4th August.

Bols was the son of a Belgian Diplomat, held dual nationality and spoke several languages. He was an experienced soldier, having fought in the Boer War, and the Dorsets benefitted from his expert leadership. We’ll hear more about the daring exploits of Bols later on.

In a flurry of activity deployments were recalled from around Ireland and reservists, usually experienced soldiers who had completed their active service, flooded into Victoria Barracks. Over half the strength of most British army battalions were reserve soldiers (590 for the 1st Dorsets). Officers were dispatched to Dorchester to collect more men. On the 9th-12th August the Battalion was sent on training and firing exercises, while the transport officers arranged passage to the front.

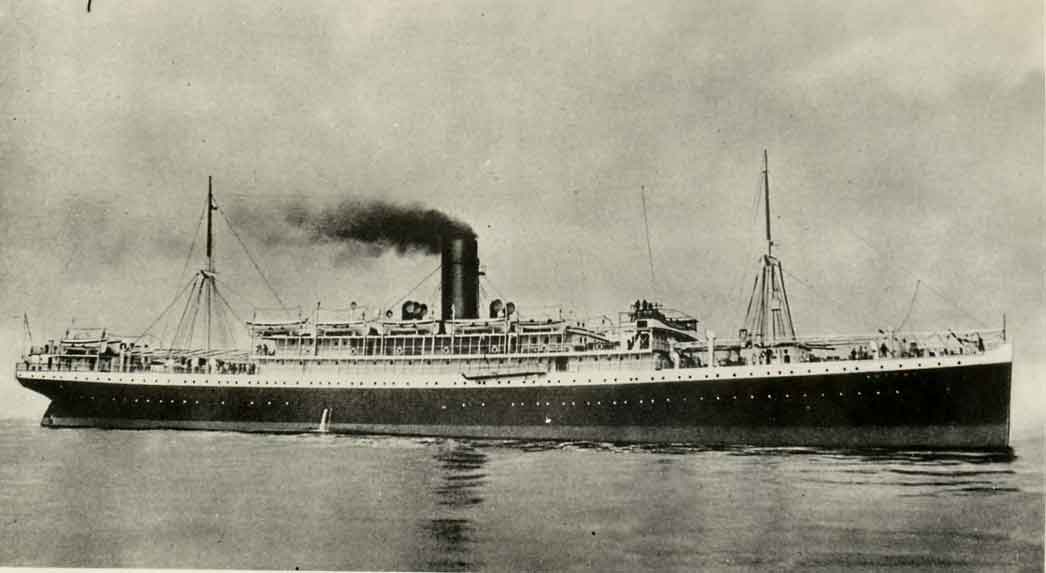

Frank wrote his letter on the day the Battalion attended a service at Belfast Cathedral. It’s hard to imagine the excitement and trepidation that Frank felt. The entire country was caught up in an outpouring of patriotic sentiment. The next day, on 14th August at 8am sharp, the Battalion loaded its transport on the the SS Antony and, at 3.25pm, she set sail in “very fine and hot” weather. The Dorsets were going to war.

All aboard for Belgium

Let us turn to the newspapers to get some idea of public opinion about the forthcoming war.

Manchester’s Guardian wrote, on the morning of 5th August 1914:

Our part in the war, for the present at any rate, is intended to be purely naval, and it is greatly to be desired that it should remain so. For the present we imagine, and we should hope later also, it is unlikely that anything will be done on land by this country.

To understand this viewpoint we must look first look at the situation in France. After their humiliating defeat at the hands of Germany in 1871, France built a standing army of about 800,000 men, which was augmented by over 2 million conscripts during August’s mobilisation, and began the war by invading Germany in a bid to regain its lost provinces of Alsace and Lorraine. This was called Plan 17. The French military leaders were convinced that the bulk of Germany’s troops were lined up directly across the French-Germany border and that fighting would be concentrated here.

In pre-war plans, Britain was asked to stand between the French left flank and the sea to the north, defending, what their leaders assumed would be, a possible secondary attack by Germany. Britain had a small expeditionary force, initially numbering about 80,000 men, rising to around 150,000 in subsequent months. Germany’s army, after mobilisation, exceeded 3 million men.

The British Expeditionary Force (BEF) was simply not equipped to deal with a full on assault by Germany’s superior numbers, and so was not expected to fulfil a central role in war on land.

Leaving his girl behind

Frank left behind his girlfriend, Jessica, in Belfast. In a thinly veiled attempt to join his loved ones together he asks his sister to write to her. He was never to see either of them again.

I have looked at the Irish Census records for 1911 to see if I could find out more about her, including a surname. The people living at 14 Maralin Street at that time do not match her name – the occupier is listed as Annie Patter but, of course, things can change in just 3 years. We’ll look at this street in a later post. Maralin Street is no longer in existence, although a Maralin Place still exists in the same area.

So on August 14th Frank left Britain, I think we can assume, for the very first time. He never returned.

Next week

The BEF moves into position in northern Belgium; a mining town by the name of Mons is their destination.