Now Till dear I want you to send me out a parcel of cake and chocolate and also a pair of socks, for our rations are very small and we get them when we can now and then they are very small, so I trust you will do your very best and send me out a parcel now and again, and I will make it right when I come back well I hope too.

19th September 1914

With the Dorsets still digging trenches along the Soissons-Sermoise road, Frank finally had some spare time in which to fill up with food. The trouble was that he has no money. So he asks his sister to help out.

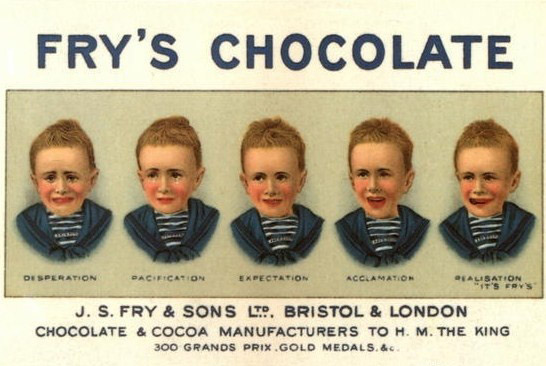

Confectionary, especially chocolate, was hugely popular in the UK. Big brands at the time included ones we love today, including Fry’s, Rowntree’s and Cadbury’s. Turkish Delight was launched in 1914, which would prove to be something of a PR disaster in the next few weeks.

The working class had seen their cost of living fall tremendously since the 1870s. Factory and technological improvements meant that, like guns and ammunition, processed foods could be made more cheaply, and in greater quantities, than ever before. This meant an increase in output of jams, sweets and chocolates towards the end of the Nineteenth Century.

The famous British sweet tooth developed long before the halcyon days of the 1920’s and 1930’s chocolate wars, so splendidly immortalised by Roald Dahl in “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory” (1964). In 1910 Woolworth’s had launched in Liverpool and Preston bringing American-style confectionaries to the British public. Pick and mix and cheap milk chocolate became tremendously popular in the UK.

Chocolate as a food stuff for troops made a lot of sense. The energy boost and nourishing effect of chocolate are undoubted. It’s only recently that they have been removed from British troops’ ration packs.

A rationale

The rations for the troops at this time were very meagre (which explains Gleichen becoming a chicken murderer).

It might have been a sport for officers foraging for food in the field. However, for the rank and file it was harder to find nourishment. Especially when few of them had any local currency. The normal rations a solder received were meant to be supplemented by iron or emergency rations but I think that, at this time, this was all the troops in the front line were getting.

A post on the excellent 1914-1918 forums describes the regulation rations given to troops in 1914.

Daily ration

This would have been given to the men whenever possible.

- 1 1/4 lb fresh or frozen meat / 1 lb preserved or salt meat

- 1 1/4 lb bread / 1 lb biscuit or flour

- 4 oz. bacon

- 3 oz. cheese

- 5/8 oz. tea

- 4 oz. jam

- 3 oz. sugar

- 1/2 oz salt

- 1/36 oz. pepper

- 1/20 oz. mustard

- 8 oz. fresh or 2 oz. dried vegetables

- 1/10 gill lime juice if fresh vegetables not issued*

- 1/2 gill rum*

- 2 oz. tobacco per week

- That’s almost a Mojito

Iron Ration

This would have been carried by a soldier in the field. I think this is all Frank was getting at the time.

- 1 lb. preserved meat

- 12 oz. biscuit

- 5/8 oz. tea

- 2 oz. sugar

- 1/2 oz. salt

- 3 oz. cheese

- 1 oz. meat extract (2 cubes.)

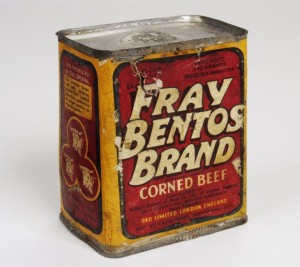

Preserved meat was generally a tin of Fray Bentos “bully beef”. You know the kind; tapered with a key in the top. Bully beef is simply corned beef, which is salted beef minced up with added fat and then compressed into a tin. The phrase “bully beef” comes from the French “bouillon beef” (boiled beef), picked up and mangled by British troops during the Crimean War. They were going to do a lot of that over the next four years.

No wonder Frank made a clarion call home for “not a fancy bit of stuff just a bit of you know the sort mate”. I know what he means: proper grub.