22nd August 1914

The Dorsets set off at 3:30am and marched 15 miles to Dour, just across the frontier in Belgium. The weather continued to be hot and even the war diary mentions how trying the march was.

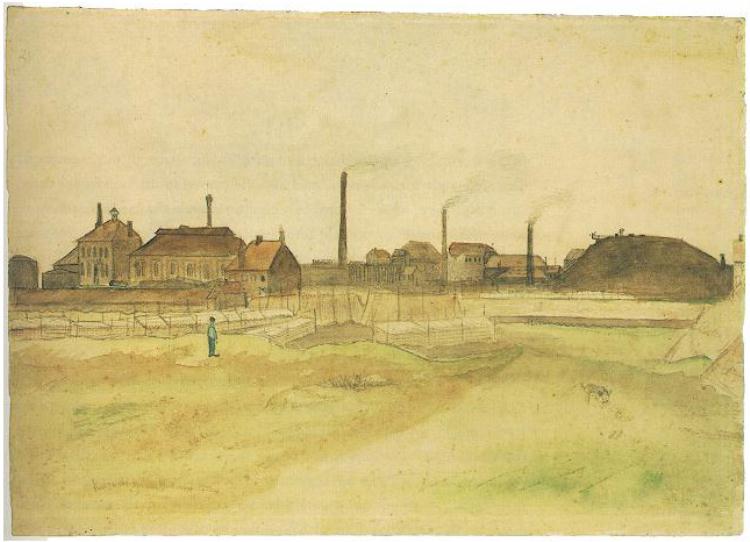

Along the way, the landscape gradually changed from bucolic countryside to a horizon dotted with slag heaps, pit heads, chimneys and tramlines.

It was hardly the ideal location for a battle. It was a far cry from the days when Marlborough and Wellington had campaigned across its lush pastures and woodlands. The Dorsets were entering “La Borinage”, a populous industrial area, which had been a muse to Van Gogh in the 1870s with its social depravation and ugliness.

Gleichen wasn’t complimentary about the location. “Any more impossible country for cavalry—except perhaps the London Docks—I have never seen.

The Dorsets billeted in Dour in the offices of a mining company. The rest of the brigade were strung out all the way up to Bois de Boussu. The BEF had finally formed up into a whole. Transport Officers like the Dorset’s Captain Hyslop were finally rejoining their units. He’d arrived in Le Havre on the 13th August and had been gallivanting around the French countryside in a “70-h.p. Daimler” organising billeting and travel arrangements for the 15th Brigade. That sounds like a terribly powerful for a car for that time. I can’t find any reference to the cars available to the 5th Division at that time, nor a 70hp Daimler having existed in 1914.

Sir John French was not planning on fighting at Mons. This was his staging area for the BEF to hook up with the French Fifth Army and attack the Germans head on.

Unfortunately the Fifth Army was being absolutely battered, and, by the end of the day, a gap had opened up between the French and the British. The Germans were pouring into the gap, unwittingly, into the path of the BEF, in an effort to outflank the French and move on Paris. Sir John grudgingly agreed with the French to stand at Mons for 24 hours.