5th November 1914

Letter to Miss M Crawshaw, 29 Strathleven – date 11 – 14 envelope franked 5 No 14 (censor no 137 still at it)

Dear Till

Many thanks for your welcome and interesting letter which I received on the 31st. I am pleased to hear that you are getting on alright and still mucking in. What’s the idea of asking me to write to your John Willie, for I don’t know him, you get him to send me out some chocolates, do you know Till that chocolate is as good as anything out here, and every one is after it.

You say what do I want for Xmas wait and see how things go for its a long way off yet, and goodness knows what will happen. Yes mate I could do with some Tooth Powder, for you should see them now they are proper gone, no I never got the toothbrush thats the only thing I never received, and I can account for that, one of our fellows took the Companies mail in the firing line and he got killed, and of course they got lost.

It is Sunday and its a fine day too and no cold tea roll on a long time. Glad to hear Tom is safe remember me to him, lets have his address and I will drop him a few lines, for thats what you look forward to more than anything else, is a letter.

Till I have forgot to tell you before, and that is that all my clothes are at Jessies home, two lots that basket and a box, I was going to send them home but we never had time wasn’t allowed out and we had to get rid of them at once. I had just bought another suit a navy blue a lovely one it cost 55/- and I only put it on twice, bowler shirts ties, socks collars watch Bank Book with 5/- in it, your hair brushes, overcoat, in fact every think. Yes I hear from Jess she sent me out a parcel not long ago, and her brother dropped me a few lines, as well, yes poor Jessies getting on alright, just as the War started I was getting on alright, at her home for I used to go round for dinner and Tea on Sundays, and supper in the week, only the old lady didn’t drink she hates the sight of it.

Well Till I am getting on alright and still in the pink, you say the war can’t last much longer don’t you believe it, for it will last longer than people think worse luck. I am still waiting to hear from your (Friend) and I have wrote to your impersonator, I mean your Johnnie. Glad to hear that Matties leg is better and that he is working, you still mucking in at Stewarts glad to hear that Ciss got my letter, I have dropped her a card since.

Remember me to all at home and I hope you are still mucking in, what time are you getting to bed, now that the pubs close at 10 o’clock. Now I think this is all the news at present trusting this finds you all in the best of health and hope to hear from you soon.

P.S. Don’t forget the tooth powder Glad Eye

I remain

your loving Brother

Bid

xxxxx

Frank wrote this letter on the 1st November, the previous Sunday, but it didn’t get posted until the 5th November. I am not sure he is in the position to be writing letters at the moment. He most probably wrote it in the morning as I would have thought he would have mentioned the bus journey if he had written it in the evening.

Mabel has presumably asked Frank to write to her boyfriend. Frank taunts her and indignantly asks for payment in chocolate. Later on in the letter he reveals that he has already written to her “John Willie”. Frank might pull a leg or two but he’s very kind at heart.

John Willie is a phrase that later became associated with John Thomas. I don’t need to explain the meaning of that, but I don’t think he’s being that crude here. In fact, there were a few songs from the time with the name John Willie in. I stumbled upon this thread of enquiry looking through the Routledge Dictionary of Slang. There was “Fetch John Willie” from 1910 and “Have you seen my John Willie” from 1914. I cannot find the lyrics to these songs but what I did find was this song by George Formby Senior. Yes, that one’s dad. He was a popular Music Hall entertainer and he played a character called “John Willie” who was “the archetypal gormless Lancashire lad … hen-pecked, accident-prone, but muddling through” (according to historian Jeffrey Richards).

Here is the 1908 song in sterophonic technicolor:

This “John Willie” is most probably the first mention of my Great Grandfather, Carl Robert Debnam. He was also in the army, a Gunner in the 41st Company, Royal Garrison Artillery. He had returned to the UK in July, after a tour of duty in Sierra Leone. He was yet to be posted to war. In fact he didn’t make it to France until late the following year. And, yes, he didn’t use his first name; everyone called him Robert (or Bob).

I’ll return to the letter tomorrow.

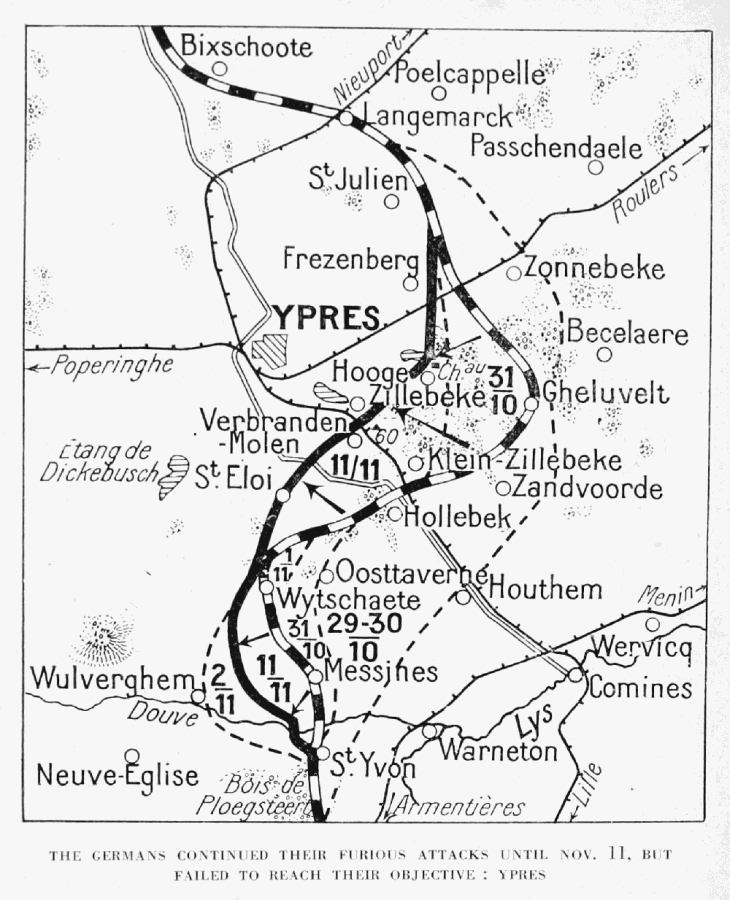

Meanwhile the Dorsets were still nervous about being next to the French, who were regularly announcing their intention to attack Messines. Further up the line they had regained a toehold in Wytschaete. In fact the 11th Brigade War Diary records that Colonel Butler reported the French were in front of the Dorsets’ trenches during the early morning of the 5th. Throughout the day different reports come in about the French preparing to attack.

Most worrying was the 8:15pm report that the Dorsets’ line had been broken, prompting Butler to send reinforcements. The Germans had attacked the Dorsets very suddenly at 7pm. The Dorsets diary reports that C Company was ordered to counter attack. After this point no indication is given of whether they regained the trench at all. It just reports that rifle fire slackened and they settled down to an eerie but quiet Guy Fawkes night shrouded in thick fog.

Elsewhere all the signs of impending trench warfare continued. The Germans were reported throwing up barricades in front of their positions opposite the Rifle Brigade who were also stationed in Ploegsteert Wood.